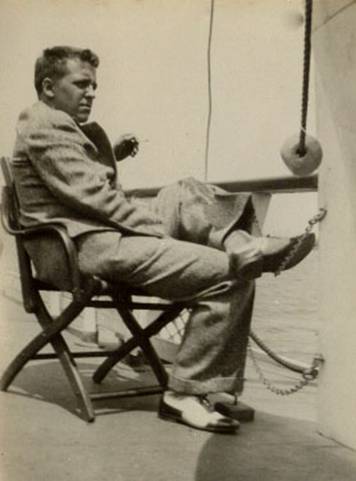

Wallace Kelly

6 reels 16mm (app. 2,000 ft.), plus preservation elements (16mm internegatives, answer prints and Digital Betacam videotapes)

In December 2007, the Librarian of Congress announced that year’s round of National Film Registry titles. Alongside OKLAHOMA! and BACK TO THE FUTURE was one otherwise unknown title, OUR DAY, an amateur film directed by Wallace Kelly. The Library’s press release read, in part:

Wallace Kelly of Lebanon, Kentucky, made this exquisitely crafted amateur film at home in 1938. “Our Day” is a smart, entertaining day-in-the-life portrait of the Kelly household, shown in both idealized and comic ways. This silent 16mm home movie uses creative editing, lighting and camera techniques comparable to what professionals were doing in Hollywood. His amateur cast was made up of his mother, wife, brother and pet terrier. “Our Day” also contains exceptional images of small-town Southern life, ones that counter the stereotype of impoverished people eking out a living during the Depression.

Although OUR DAY was, on one hand, a record of small-town American life of the time, it caught the attention of modern audiences and the National Film Preservation Board not because of its role as a sociological and historical document, but rather because of Wallace Kelly’s superior aesthetic sense. Dave Kehr, National Film Preservation Board member and film critic for the New York Times, wrote that it “displays a more sophisticated sense of mise-en-scène than the great majority of current Hollywood features.” Dan Streible, the NFPB member who saw the film at its first-ever public showing in 2007, without any sense of exaggeration compared it to Gregg Toland’s cinematography on CITIZEN KANE three years later.

OUR DAY was arguably Kelly’s cinematic masterwork and it has received the bulk of the acclaim from the few contemporary audiences that have seen his films, but a review of his entire collection reveals that he was an accomplished filmmaker from the very first time he picked up a movie camera. Though never a professional filmmaker, Kelly was a first-rate self-taught artist in many media, and his work both on film, on the printed page and on canvas during the 1930s reveals a deep feeling for the modernism of the time. His renown as a painter continues throughout Kentucky to this day, and a Louisville gallery that exhibits and currently sells his paintings says that he “created some of the best WPA-era images of life in Kentucky.”

Wallace Kelly’s films are significant in part due to their contents and the way they document Depression-era American scenes, but more importantly because of the way they show his unsurpassed aesthetic skills as a movie hobbyist. Kelly’s filmmaking resembles many of the most accomplished films of the Amateur Cinema League members of his time, and betters them in many ways. Remarkably, though, Kelly was not a cine-club member and he did not seek out audiences for his films other than family members and neighbors.

While Kelly lived in a small town most of his life, he was no naïf, and he was just as at home in cosmopolitan settings as well as the back roads of America, and he brought his painterly eye to each setting equally.

About Wallace Kelly

Wallace Kelly (1910-1988) was born in Lebanon, Kentucky, a town settled by his ancestors in the 18th century. He attended Center College and the Cincinnati Art Academy. In 1929 he moved to New York to pursue a career as a book illustrator. There he bought his first movie camera, skipping lunch for a year to pay for it.

While in New York, he toyed with the idea of being an actor and he “starred” as the young love interest in a local advertising film called The Story of Astoria. He had been cast by the Provincetown Players when bad news came from Kentucky, and because of the death of his father, a newspaper publisher, Wallace returned to Lebanon to help run the family business and maintain their homeplace.

In 1935, Wallace and his fiancée Mabel Graham entered the Newspaper National Snapshot Awards contest and won first prize. Following their marriage in 1936, they studied portrait photography in New York before returning to Lebanon to open a studio.

In 1940, Wallace received another prize that changed his life when his novel, Days are as Grass, won the first Alfred A. Knopf Fellowship. As a result, he closed the photographic studio to devote his time to writing. With the outbreak of World War II, he joined the service and served as a medic in the South Pacific. After the war he returned to Kentucky, where he spent the rest of his life painting and creating graphics.

Wallace made 16mm movies from 1929 through about 1950. Most of them are of family trips and home events. Several travel films and a five-part year-by-year series of his baby daughter Martha are carefully titled, some with stop-frame animation. Two, OUR DAY and THE ENTERPRISE GOES TO PRESS, are fully scripted narratives.

About the Films

The sophisticated “city symphony” imagery of WALLACE GOES TO NEW YORK belies the facts that not only was it most likely among the first rolls of film he had ever shot, but also that he was still in his teens when he began filming. The film documents his move from Kentucky to New York City and his adventures there, with shots of Times Square at night, elevated trains and city streets, and shots of the filming of the local dramatic film A STORY OF ASTORIA.

Eight years later (in the same year he made OUR DAY), Kelly produced THE ENTERPRISE GOES TO PRESS. The Lebanon Enterprise was the family-run business and Kelly used the setting for a well-crafted documentary following the production of a small town newspaper, from the linotype operator to the handbill press operator to the editor proofreading galleys. All in all, it is a significant example of the amateur industrial film, a too-often overlooked form that offers an interesting and different perspective on the sponsored industrial film genre.

TRIP TO THE YELLOWSTONE (1937), FAMILY TRIP WEST (1939), are superlative examples of Kelly’s amateur travel films. Like countless other home movie makers, Kelly eagerly got out his 16mm camera when it came time for family trips. These two were selected from numerous other travel reels because these voyages captured many of the most iconic settings of the American West—including stunning scenes of the family clambering around on the faces of Mount Rushmore while it was under construction. Kelly crafted the 1937 reel with titles reflecting his literary bent, and both films are superior examples of how Kelly could bring his photographer’s perspective to landscape scenes.

KELLY SCRAP BOOK (1930s) is an “odds and ends” reel of outtakes and other clips edited by Kelly.